In the first part, Helen includes extracts from Laurence Durrell’s Avignon Quintet, from Moby Dick by Herman Melville, and from a short story by MFK Fisher.

The Avignon Quintet by Lawrence Durrell

Probably my favourite author. Our favourite books may not be the ones that we think are the most brilliant. I love many books simply because of the time that I read them and the lasting impact they made. I read theAlexandria Quartet when I was eighteen, a reluctant law student and taking a summer job as a cleaner in a hospital. I read it in my breaks, in between mopping floors, washing dishes for a ward of twenty patients and cleaning vegetables. The glamour swept me away. Leaning on my mop I would be transported to the Corniche at night, picturing myself as Justine, striding into a nightclub, wearing emeralds and a sharkskin suit. I also transported myself to the desert and the marshes.

Probably my favourite author. Our favourite books may not be the ones that we think are the most brilliant. I love many books simply because of the time that I read them and the lasting impact they made. I read theAlexandria Quartet when I was eighteen, a reluctant law student and taking a summer job as a cleaner in a hospital. I read it in my breaks, in between mopping floors, washing dishes for a ward of twenty patients and cleaning vegetables. The glamour swept me away. Leaning on my mop I would be transported to the Corniche at night, picturing myself as Justine, striding into a nightclub, wearing emeralds and a sharkskin suit. I also transported myself to the desert and the marshes.

Durrell’s language is wonderful. He is also terribly funny. His descriptions of Scobie and Pombal are hilarious and touching. I must have read it ten times. As I grew older I became more perturbed by his ambivalent attitude to women. Without exception, each one of his female characters who he admires or loves, is either lesbian (a trait that he seems to fear) comes to a sticky end or to his evident relief has her looks ravaged by time. Nevertheless it would be my desert island book.

My first entry is from the Avignon Quintet, just because I'm reading it at the moment. Durrell explores his fascination with Gnosticism at greater length, which baffles and almost bores me, but it is still a terrific read.

Two extracts from the Quintet

From Livia:

Felix is the British Consul in Avignon, a lowly, unpaid post that leaves him living a lonely life but still required to fly the flag and avoid any scandal. The only perk that he gets is the periodic delivery via the Crown Agents of a box containing items that he has requested. These boxes were known throughout the service as “Consolation Prizes – consoling one against the horrors of foreign residence among the lesser breeds of the Kipling kind or simply among backward European states, like France with its frogs legs and polluted water.” His contains booze and also:

“On the kitchen table stood a tin of Bumpstead’s Bloater paste beside a bottle of Gentleman’s Relish and Mainwearing’s Pickle Mix. The consul sat down and stared hard at these sterling products. Imperial Anchovies, Angostura Bitters, Pork and Beans, Imperial Size. Lea and Perrins sauce… A profound homesickness overcame him… He started to unpack the crate and put the pots in the cupboard, arranging them like a fussy old maid so that their names were facing outward. Then a sudden impulse overcame him and he did something he should never have done; he smeared bloater paste on his croissant and ate it with a groan. It was delicious.”

There is a spectacular description of a banquet at the end of Livia but I'll save it for later.

As a complete contrast, here is a description of a Christmas feast at a chateau from Monsieur:

“Its floor was laid with large grey stone slabs which were strewn with bouquets of rosemary and thyme… the high ceiling was supported by thick smoke-blackened beams from which hung down strings of sausages, chaplets of garlic and numberless bladders filled with lard… Along the wide shelf above the fire were rows of objects at once utilitarian and intriguing because beautiful, like rows of covered jars in pure old faience ranging in capacity from a gill to three pints and each lettered with the name of its contents — saffron, pepper, cumin, tea, salt, flour, cloves.

But the wine was going about now and the most important supper of the whole year was in full sail. By old tradition is has always been a 'lean’ supper, so that in comparison with other feast days it might have seemed a trifle frugal. Nevertheless the huge dish of “raito” exhaled a wonderful fragrance; this was a ragout of mixed fish presented in a sauce flavoured with wine and capers. Chicken flamed in cognac. The long brown loaves cracked and crackled under the fingers of the feasters like the olive branches in the fireplace. The first dish emptied at record speed and its place was taken by a greater bowl of Rhone pan fish, and yet another of white cod. These in turn lead slowly to dishes of snails, the whiteish large veined ones that feed on vine leaves. They had been tucked back into their shells and were extracted with the aid of strong curved thorns, three or four inches long, broken from the wild acacia. As the wine was replenished after the first round toasts began to fly around.

Then followed the choice supporting dishes, large white “cardes” or “cardons”, the delicious stem of a giant thistle which resembles nothing so much as an overgrown branch of celery. These stems are blanched and then cooked in white sauce — I have never tasted them anywhere else. The flavour is one of the most exquisite one can encounter in the southern regions of France, yet it is only a common field vegetable. So it went on, our last dinner, to terminate at last with a whole anthology of sweetmeats and nuts and winter melons. The fire was restoked and the army of wine bottles gave place to a smaller phalanx of brandies, Armagnacs and Marcs, to offset the large bowls of coffee from which rose plumes of fragrance.”

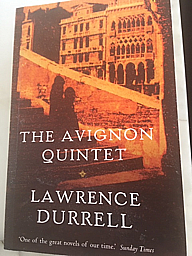

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

The word “genius” (clever), like “passionate” (keen on), “tragic” (sad), “ashamed” (embarrassed) and so many others, is over used but I believe that Moby Dick is a work of genius and unlike anything else. I read it from cover to cover for the first time only last year and in a perfect setting, a shack on the beach at Dungeness at the beginning of winter. One test of a great book for me is whether I need to own a fine edition, because I know that I will want to read it over and again. When I got back from Dungeness I tracked down and bought an old Folio edition.

The word “genius” (clever), like “passionate” (keen on), “tragic” (sad), “ashamed” (embarrassed) and so many others, is over used but I believe that Moby Dick is a work of genius and unlike anything else. I read it from cover to cover for the first time only last year and in a perfect setting, a shack on the beach at Dungeness at the beginning of winter. One test of a great book for me is whether I need to own a fine edition, because I know that I will want to read it over and again. When I got back from Dungeness I tracked down and bought an old Folio edition.

Food doesn’t feature much in Moby Dick, for the whalers it’s just fodder, but at the beginning of the book, before Ishmael and Queequeg board the "Peequod", they spend the night in Nantucket at the Try Pots Inn.

“… two enormous wooden pots painted black, and suspended by asses’ ears swung from the cross-trees of an old top-mast planted in front of an old doorway. The horns of the cross-trees were sawn off on the other side, so that this old top mast looked not a little like a gallows. Perhaps I was over sensitive to such impressions at the time but I could not help staring at this gallows with a vague misgiving…

Upon making known our desires for supper and a bed, Mrs Hussey (the landlady) suspending further scolding for the present ushered us into a little room and seating us at a table spread with the relics of a recently concluded repast turned round to us and said — Clam or Cod?...

Queequeg said, ‘Do you think we can make out a supper for us both on one clam?’

However, a warm savoury steam from the kitchen served to belie the apparently cheerless prospect before us. But when that smoking chowder came in, the mystery was delightfully explained. Oh! Sweet friends hearken to me. It was made of small juicy clams, scarcely bigger than hazel nuts, mixed with pounded ships biscuits, and salted pork cut up into little flakes; the whole enriched with butter, and plentifully seasoned with pepper and salt”

The two polish off their clam chowder and then:

“I thought I would try a little experiment. Stepping to the kitchen door, I uttered the word cod with great emphasis, and resumed my seat. In a few moments the savoury steam came forth again, but with a different flavour, and in good time a fine cod chowder was placed before us.

Fishiest of all fishy places was the Try Pots which well deserved its name; for the pots there were always boiling chowders. Chowder for breakfast, and chowder for dinner, and chowder for supper, till you began to look for fish bones coming through your clothes. The area before the house was paved with clam shells. Mrs Hussey wore a polished necklace of codfish vertebrae; and Hosea Hussey had his account books bound in superior old sharkskin. There was a fishy flavour to the milk too, which I could not at all account for till one morning happening to take a stroll along the beach among some fishermen’s boats, I saw Hosea’s brindled cow feeding on fish remnants, and marching along the sand with each foot in a cod’s decapitated head, looking very slip shod I assure you.”

MFK Fisher

MFK Fisher is one of my heroines. A food writer but so much more than that. Her body of work is huge and I think I have read and I own all of it. John Updike called her “A poet of the appetites” and WH Auden who wrote the introduction to her book The Art of Eating said “I do no know of anyone in the United States today who writes better prose”. The New York Times Book Review wrote that “In a properly run culture, Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher would be recognised as one of the great writers this country has produced in this century.”

MFK Fisher is one of my heroines. A food writer but so much more than that. Her body of work is huge and I think I have read and I own all of it. John Updike called her “A poet of the appetites” and WH Auden who wrote the introduction to her book The Art of Eating said “I do no know of anyone in the United States today who writes better prose”. The New York Times Book Review wrote that “In a properly run culture, Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher would be recognised as one of the great writers this country has produced in this century.”

Among other things she writes of what it was like to live in the South of France in the 40’s and 50’s, of the kitchens that she used, some consisting of little more than an alcove in the corner of a single room with a window sill for larder, of bringing up and travelling with two little girls and introducing them to good food, of what it’s like to stay in hotels and dine by yourself, and of how to eat well, when you have to walk and bus it into the nearest village in Provence and carry a weeks shopping home in string bags and the sun is so strong that your fruit is beginning to rot before you get it home.

She also wrote at least one novel and very many short stories. This is one of my favourites, which also shows the discrimination and originality of her attitude towards food.

From “A Kitchen Allegory”, part of the collection titled Sister Age.

Mrs Quale lives alone. She cares about food but has slipped into a routine that works well for her:

“… a salutary mishmash of green beans, zucchini, parsley and celery, which she made once or twice a day in a pressure cooker. She drained the juices from this concoction and drank them when she felt queer, between bowlsful of the main bulk. She believed, temporarily anyway, that she got everything that she needed — whatever that was — and she lost pounds from this regime and felt rather pure and noble.”

Then one day, her daughter who she rarely sees, tells her that she is coming with her little boy for a week end. Mrs Quayle goes marketing for:

“… her darling girl… She bought madly and stupidly more than could possibly be eaten in a week by five people, in a masochistic flurry of wishful child feeding.”

She knows that her daughter is on a permanent diet, yet she:

“… bought cartons full of affront to her child’s philosophy, so that by the time the little family was together there was a newly dusted cookie jar full of strange rich temptations all loaded with butter and sweetness; there was bread for toast, which she herself had not eaten for months; marmalade and strawberry preserves were ready to the hand. In the crammed ice box there were bowls of freshly chopped beef, prawns cooked correctly (which is to say in family fashion) and peeled and ready, fresh mayonnaise, and far at the back, a lost bowl of her own mashed vegetables. Clean lettuces lay ready in the crisping drawers. Did the girl want coffee overroast, freshly ground, decaffeinized, powdered? There was milk, both homogenized and “slim”. There were pounds of sweet butter, of course. And on the sideboard there were bananas and papayas and lemons and tangelos for the dear little boy. There were little pink new potatoes to cook in their luminous skins.

There was some really fine garden-green asparagus, which Mrs Quayle’s daughter used to love, and then a block of excellent Teleme Jack cheese — something of a rarity. There were fresh bright strawberries in a bowl, ready to be washed at the last minute, but in case the girl’s old passion for tapioca pudding still waxed, four little Chinese bowls of it were ready, too, and a couple of bottles of white wine, the favourite ones, and a Grignolino on the counter when the time came for a boeuf tartare or a grilled hamburger…”

As you have probably guessed the visit is a tragic (truly — see Moby Dick above) disappointment. They only stay a few hours and she is left heartbroken acknowledging that:

“… the girl was leaving with the baby to join life again, far away, where other things would feed her, leaving her with all that food that “must be destroyed, before it could hurt other people.”

However she rallies herself:

“She made a little drink first, and then, without paying any attention, she started the water for her special way of making asparagus on toast somewhat intricate but worth the bother and a meal in itself. She opened the bottle of Folle French and put it back in the ice-box to wait until she had finished her gin-and-It, and then set a place nicely at the kitchen table, with two wine glasses, in case she wanted a little Grignolino after the white. She made a salad from the hearts of the lettuces she had cleaned (She loved the hearts best, but most of her life had given them to other people because they did, too). Then she deftly put together a beoeuf tartare as she had done for a thousand years.”

She sits down to eat:

“A plate arranged almost correctly in the Japanese style was at her place on the table, with five prawns, three halves of green olives and a curl of celery upon it to amuse her. The boeuf tartare bound with olive oil and seasoning, with the yolk of half an egg in its shell on top, like a jaundiced eye, waited on the sideboard. There was buttered toast in the warm oven for the asparagus … Later, she would make coffee, and eat one of the candies, a tricky little block of mint and black chocolate.”

There a twist to this story though. She feels no self pity but instead, experiences a sudden sensation of “real violence, like walking into a closed door in the dark”, at the thought of her daughter’s selfishness. She allows herself a few seconds of anger, looks at the:

“… nicely set table and the simmering things on the stove and she listened to the icebox humming to keep the other supplies dormant, and she decided, without further thought or doubt, to turn off the whole silly business and go to bed.”

The next morning she makes another pot of her “mishmash” and takes the salvageable food to friends who were “getting too stiff to do their own marketing”.

It’s a fine piece of writing, although I really wish that she had allowed herself a fine dinner.