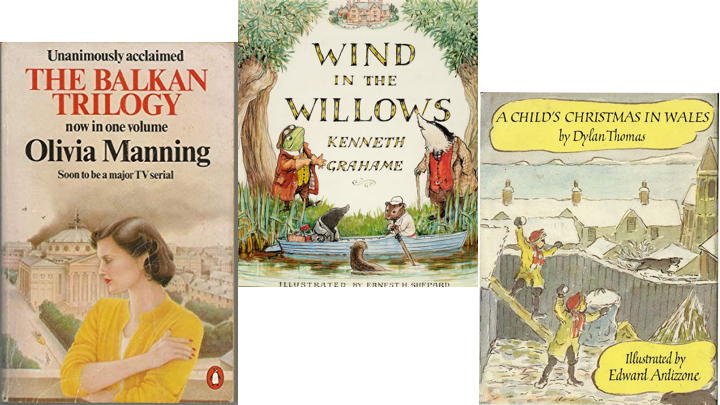

In the second set of extracts for winter and Christmas, Helen has chosen: the Christmas Eve at Mole’s house in The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Graham; Harriet Pringle’s first banquet in The Balkan Trilogy by Olivia Manning; and A Child’s Christmas in Wales by Dylan Thomas.

The Wind In The Willows by Kenneth Graham

Food is very important to Ratty and Mole. The animals' lifestyle and diet is that of Edwardian bachelors. (There are only two female characters in the book and they are both humans; the gaoler’s daughter, who helps to spring Toad and the bargee washerwoman.) The most well known scene featuring food is the description of Ratty’s glorious picnic basket. However, I’m including the scene where Mole returns home, after spending many weeks with Ratty. His house has been neglected and the two animals set to, restoring it to order and are about to dine on the contents of the store cupboard, “a tin of sardines – a box of captain’s biscuits, nearly full—and a German sausage encased in silver paper,” washed down with bottled beer.

They are congratulating each other and are just about to set to, when they hear scuffling noises outside the front door and it suddenly dawns on them that it’s Christmas Eve and the that the fieldmice have come to carol sing.

It was a pretty sight, and a seasonable one that met their eyes when they flung the door open. In the forecourt, lit by the rays of a horn lantern, some eight or ten little fieldmice stood in a semi circle, red worsted comforters round their throats, their forepaws thrust deep in their pockets, their feet jigging for warmth. With bright beady eyes they glanced shyly at each other, sniggering a little, sniffing and applying coat sleeves a great deal. As the door opened, one of the older ones who carried the lantern was just saying, “Now then, one, two three!” and forthwith their shrill little voices up rose on the air, singing one of the old-time carols that their forefathers composed in fields that were fallow and held by frost, or when snowbound in chimney corners, and handed down to be sung in the miry street to lamp-lit windows at Yule-time.

After the carol Ratty heartily invites them in to warm themselves, but Mole is distraught when he remembers that they have no food to offer them.

“You leave all that to me,” said the masterful Rat. “Here, you with the lantern! Come over this way. I want to talk to you. Now, tell me, are there any shops open at this hour of the night?”

“Why, certainly sir” replied the fieldmouse respectfully. “At this time of the year our shops keep open to all sorts of hours.”

“Then, look here!” said the Rat “You go off at once, you and your lantern, and you—”

Here much muttered conversation ensued, and the Mole only heard bits of it, such as “—fresh, mind!—no, a pound of that will do—see you get Buggins’s, for I won’t have any other—so, only the best—if you can’t get it there, try somewhere else—yes, of course home made, no tinned stuff—well, then do the best you can!” Finally there was a chink of coin passing from paw to paw, the fieldmouse was provided with an ample basket for his purchases, and off he hurried, he and his lantern.

The Rat meanwhile was busy examining the label on one of the beer bottles. “I perceive this to be Old Burton,” he remarked approvingly. “Sensible Mole! The very thing! Now we shall be able to mull some ale! Get the things ready Mole while I draw the corks.”

It did not take long to prepare the brew and thrust the tin heater well into the red heart of the fire; and soon every fieldmouse was sipping and coughing and choking (for a little mulled ale goes a long way) and wiping his eyes and laughing and forgetting that he had ever been cold in all his life.

Then:

… the door opened and the fieldmouse with the lantern reappeared, staggering under the weight of his basket.

There was no more talk of play acting once the very real and solid contents of the basket had been tumbled out on the table. Under the generalship of Rat, everybody was set to do something or to fetch something . In a very few minutes supper was ready, and Mole, as he took the head of the table in a sort of dream, saw a lately barren board set thick with savoury comforts; saw his little friends' faces brighten and beam as they fell to without delay; and then let himself loose—for he was famished indeed—on the provender so magically provided, thinking what a happy home coming this had turned out, after all.

The fieldmice:

…clattered off at last, very grateful and showering wishes of the season, with their jacket pockets stuffed with remembrances for the small brothers and sisters at home. When the door had closed on the last of them and the chink of the lanterns had died away, Mole and Rat kicked the fire up, drew their chairs in, brewed themselves a last night cap of mulled ale, and discussed the events of the long day. At last the Rat, with a tremendous yawn, said, “Mole old chap, I’m ready to drop. Sleepy is simply not the word. That your bunk over on that side? Very well then, I’ll take this. What a ripping little house this is! Everything so handy!”

He clambered into his bunk and rolled himself well up in the blankets, and slumber gathered him forthwith, as a swath of barley is folded into the arms of the reaping machine.

The weary Mole also was glad to turn in without delay, and soon had his head on his pillow, in great joy and contentment. But ere he closed his eyes he let them wander round his old room, mellow in the glow of the firelight that played or rested on familiar and friendly things which had long been unconsciously a part of him, and now smilingly received him back, without rancour.

The Balkan Trilogy by Olivia Manning

Another of my ten most loved novels.

It is 1939. Harriet has just married Guy Pringle and travelled to join him and to start married life in Bucharest, where he works for the British Council. The war has just begun and every day the news seems worse, as the Germans continue in what seems like an unstoppable invasion of all of Europe.

The Pringles socialise with an eclectic collection of diplomats, Romanians, British Council staff and exotic refugees.

Harriet has rented a flat for herself and Guy and engaged a maid, the priceless Despina. She decides to hold their first dinner party on Christmas night. The guests are:

- Prince Yakimov, an effete Russian who is a refugee, penniless, and a consummate scrounger;

- Bernard Dugdale, a diplomat passing through on his way to Ankara, who no one else knows and who Yakimov brings with him, without asking first;

- Clarence Lawson, an emotional young man, who also works for the British Council and is deployed at the British Propaganda Bureau;

- Professor Inchcape of the British Council;

- Bella, Harriet's friend, a wealthy British expat;

- Nikko, Bella's Romanian husband, another uninvited guest, who has appeared in Bucharest without warning.

Most of the guests either do not know or like each other, or both. The conversation is stilted and riven with misunderstanding and the evening is a social disaster.

Despina, enjoying her own resource, collected the smaller chairs from under the guests and took them to the table, then she sung out “Poftiti la masca.” On the table, among the Pringles' white china and napkins, were two yellow plates with pink napkins. Among the six chairs were the kitchen stool and the cork topped linen box from the bathroom. This was the first dinner party Harriet had ever given. She could have wept at its disruption.

When they were all seated, there was not much elbow room at the table. Nikko, pressed up against Yakimov, kept giving him oblique glances and at last blurted out: “I have heard of the famous English prince who is so spirituelle.” Everyone looked at Yakimov, hoping to get entertainment, but his eyes were fixed on Despina, who was carrying round the soup. When the bowls reached him, he filled his plate eagerly and emptied it before Guy had been served. He then watched for more.

The conversation is stilted and Yakimov distinguishes himself by shamelessly helping himself to the largest and best portions of everything, totally regardless of others. This makes Harriet and the loyal Despina livid.

Despina had cut more turkey and was carrying the large serving dish round again. When she came to Yakimov, she held it so that the white meat was out of his reach.

“Just a soupçon, dear girl,” he said, with an air of wheedling intimacy and, stretching out his arms. He again took most of the breast. Only a few vegetables remained. He took them all. Despina, hissing through her teeth, attracted Harriet’s attention and pointed to his plate. Harriet waved her on. Only Yakimov, intent on his food, was unaware of Despina’s indignation. He ate at speed, wiped his mouth with his napkin and looked around to see what was coming next.

Guy, having anticipated an evening of Yakimov’s wit, now tried to encourage him to talk by telling stories himself. When his stories were exhausted, he started on limericks, occasionally pausing to ask Yakimov if he could think of any himself. Yakimov shook his head. Despina, having brought in a large mince pie, he could attend to nothing else.

Guy searched his mind for limericks and remembered one that he thought would seem particularly fun to the company. It concerned the morals of a British diplomat in the Balkans.

“That” said Dugdale coldly, “seems to me in rather bad taste.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” said Yakimov heartily.

For some minutes there was no sound but that of Yakimov bolting down pie. He finished his helping before Despina had completed serving the others. “Hah!” he said, with satisfaction and, unimpaired, looked to her for more.

As soon as was possible, Harriet motioned Bella to retire with her to the bedroom. There, not caring whether she was overheard or not, she raged: “How dare he snub Guy! The gross snob, wolfing down our food, and bringing that dyspeptic skeleton with him. When he gave his tremendous parties—if he ever gave them, which I doubthe would not have dreamt of inviting us. Now he entertains his friends at our expense.”

Bella was quick to echo this indignation: “If I were you my dear I wouldn’t ask him here again.”

“Certainly not” said Harriet, dramatic in anger, “this is the first and last time he sets foot in my house.”

When the women returned to the room, the men were gathered round the electric fire. Guy was helping Yakimov to brandy. Dugdale, unperturbed, was sprawling in the armchair again. At the entry of the women, he shifted himself slightly, and was about to drop back, when Harriet pushed the chair from him and offered it to Bella. He took himself to another chair with the expression of one overlooking a breach of good manners.

Inchcape smiled maliciously at Harriet, then turned to Yakimov and asked him: “Are you going on later to Princess Teodorescu’s party?”

Yakimov lifted his nose from his glass. “I might,” he said, “but those parties come a bit rough on your poor old Yaki.”

This is another book that was brilliantly dramatized by the BBC in 1987, with Emma Thompson and Kenneth Brannagh as Harriet and Guy and Ronald Pickup as Prince Yakimov.

A Child’s Christmas in Wales by Dylan Thomas

Like Dylan Thomas, I grew up in West Wales, and his Christmas Day is very familiar to me, especially when he evokes the atmosphere of overheated and overcrowded dining and sitting rooms and the soporific effects of huge amounts of food and drink.

On Christmas morning Dylan’s presents included sweets;

Hardboileds, toffee, fudge and allsorts, crunches, cracknels, humbugs, glaciers, marzipan, and butterscotch for the Welsh… And a packet of cigarettes. You put one in your mouth and you stood at the corner of he street and you waited for hours, in vain, for an old lady to scold you for smoking a cigarette, and then with a smirk you ate it. And then it was breakfast under the balloons."

For dinner we had turkey and blazing pudding, and after dinner the uncles stood in front of the fire, loosened all buttons, put their large moist hands over their watch chains, groaned a little and slept. Mothers, aunts and sisters scuttled to and fro, bearing tureens. Auntie Bessie, who had already been frightened, twice, by a clock work mouse, whimpered at the sideboard and had some elderberry wine. The dog was sick. Aunty Dosie had to have three aspirins, but Auntie Hannah, who liked port, stood in the middle of the snow bound back yard, singing like a big-bosomed thrush. I would blow up balloons to see how big they would blow up to; and, when they burst, which they all did, the uncles jumped and rumbled. In the rich and heavy afternoon, the uncles breathing like dolphins and the snow descending, I would sit among festoons and Chinese lanterns and nibble dates and try to make a model man o'war following the instructions for Little Engineers, and produce what might be mistaken for a seagoing tramcar."

And then at tea the recovered uncles would be jolly and the iced cake loomed in the centre of the table like a marble grave. Auntie Hannah laced her tea with rum because it was only once a year.

Bring out the tall tales now that we told by the fire as the gaslight bubbled like a diver. Ghosts whooed like owls in the long nights when I dared not look over my shoulder; animals lurked in the cubbyhole under the stairs where the gas meter ticked.

And always on Christmas night there was music. An uncle played the fiddle, a cousin sang Cherry Ripe and another uncle sang Drake’s Drum. It was very warm in the little house. Auntie Hannah, who had got on to the parsnip wine, sang a song about bleeding hearts and death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a bird’s nest and everyone laughed again; and then I went to bed. Looking through my bedroom window, out into the moonlight and the unending smoke-coloured snow, I could see the lights in the windows of all the other houses on our hill and hear the music rising from them up the long, steadily falling night. I turned the gas down, I got into bed, I said some words to the close and holy darkness, and then I slept.